Presidents and religion

The Founding Fathers had competing views on religion in public life

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

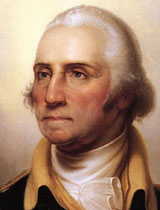

† In his Farewell Address to the nation, George Washington said, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.”

§ Thomas Jefferson wrote, in an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association of Connecticut, that “religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship.” Further, Jefferson interpreted the First Amendment as “building a wall of separation between church and State.”

‡ Abraham Lincoln, in the depths of the Civil War, wondered out loud how both sides of the conflict could reasonably claim to have God on their side: “Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces,” Lincoln said in his Second Inaugural Address.

Despite these widely varying perspectives on God and religion, many find it convenient to invoke a particular president or Founder to support their own position on religion in public life, as if the selected view were the view. Depending on who is being quoted and in what context – or out of context – the U.S. might come out as a “Christian nation,” a secular state, or even a state that is purportedly at war with religion (as in the culture wars).

In fact, the Founders, like Americans today, had diverse and complex views on the subject. Some, like Patrick Henry, favored greater inclusion of religion in public life, while others – most notably James Madison – favored less. The First Amendment was designed to balance these competing interests. A national religion was out of the question, since there were so many different competing Protestant groups at the time, and many states still maintained their own official state religious establishments. Hence, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” Restrictions on particular religious practices were equally unfeasible and unacceptable. Therefore, the new federal government was also barred from “prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The First Amendment was the means by which the Founders agreed to disagree. The principles contained in it are broad, and the Founders left it up to future generations to work out the details.

In modern times, when arguing matters of religion and politics, it is always tempting appropriate the words of one's favorite Founder to support a particular position, when, in fact, the Founding Fathers had complex and oftentimes competing views – which can only be understood in full context.

The Founders' philosophies – and how they are applied today – are further examined in the University of Massachusetts Press book, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective by Bruce T. Murray.

“It seems necessary, then, that the history and current concerns regarding religious freedom in America be clearly understood prior to weighing in on the contentious contemporary debates. This is precisely the task of Bruce T. Murray's Religious Liberty in America; one that he accomplishes with impartiality and insight.”

—Brandon M. Crowe, Ph.D., School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Arizona State University

(from Reviews in Religion & Theology, History and Sociology of Religion, Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Vol. 17, Issue 2, 2010)

Religious Liberty in America is available at numerous university libraries, and it may be purchased from the University of Massachusetts Press.

Read about the author here.