Originalism and the uses and abuses of history

Justices Sam Alito and Clarence Thomas were instrumental in expanding the constitutional limits of individual gun ownership.

Justices Sam Alito and Clarence Thomas were instrumental in expanding the constitutional limits of individual gun ownership.For Supreme Court justices who follow ‘originalist’ thinking, history reveals the law

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

In a landmark 2010 case, the Supreme Court looked to history as one of its primary barometers to gauge whether gun ownership is a fundamental right that state governments may not violate through regulation. In McDonald v. Chicago, the justices devoted substantial verbiage to tracing the history of gun ownership in the United States, particularly as the right to bear arms applied — and was denied African-Americans during the period immediately following the Civil War.

— Justice John Paul Stevens, dissenting

The Court’s extensive historical analysis follows the tendency of some conservative members of the Court to follow an “originalist” theory of the Constitution — the belief that the meaning of the Constitution is best understood through the original intent of the framers. In order to discern this intent, it is often necessary to explore the history and debates during the founding period.

— Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the Court

In the McDonald case, the Court looked not only to the late 1780s, when the Constitution and Bill of Rights were drafted, but perhaps more importantly to the late 1860s, when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted. The Fourteenth Amendment provided the basis for incorporating the Bill of Rights; therefore the Court majority considered that historical period highly relevant.

Justice Clarence Thomas, in his concurring opinion, devotes a substantial portion of his analysis to surveying the circumstances of African-Americans before and after the Civil War. African-American history during the period of Reconstruction also figures prominently in Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion.

— Justice Stephen Breyer, dissenting

(Stevens' and Breyer's dissenting opinions are discussed more fully below, while this article will begin by exploring the majority's reasoning.)

The Reconstruction period

As Alito and Thomas describe, during the period immediately following the Civil War, white militias in the South frequently harassed, killed and disarmed freed slaves and former African-American soldiers who had fought for the Union. Several Southern states enacted laws prohibiting African-Americans from possessing firearms, depriving them of self-defense. An unincorporated Second Amendment allowed the states to freely enact such measures.

Setting the scene in 1865, Justice Alito quotes Senator Henry Wilson, a Republican from Massachusetts, from the 39th Congress: “In Mississippi, rebel State forces — men who were in the rebel armies — are traversing the State, visiting the freedmen, disarming them, perpetrating murders and outrages upon them; and the same things are done in other sections of the country.”

In response to this situation, Congress passed the Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1866 and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which sought to extend civil rights to the recently emancipated slaves, including the right to keep and bear arms. These measures were insufficient, according to Alito, and Congress pushed forward with a constitutional amendment to provide full weight to the protections for African-Americans. To show the importance of bearing arms, Alito quotes Senator Samuel Pomeroy during the debate over the Fourteenth Amendment:

“Every man … should have the right to bear arms for the defense of himself and family and his homestead. And if the cabin door of the freedman is broken open and the intruder enters for purposes as vile as were known to slavery, then should a well-loaded musket be in the hand of the occupant to send the polluted wretch to another world, where his wretchedness will forever remain complete.”

This and further historical testimony, Alito wrote, “only confirm that the right to keep and bear arms was considered fundamental. In sum, it is clear that the Framers and ratifiers of the Fourteenth Amendment counted the right to keep and bear arms among those fundamental rights necessary to our system of ordered liberty.”

In addition to the historical connection to the legal issues involved, Alito applies the factual circumstances of the McDonald case to the history. The plaintiff, Otis McDonald, an African-American in his late-seventies, challenged Chicago’s handgun ban because he wanted to keep a gun in his house for self-defense — in this case, not from white mobs but from urban gangs and criminals. Alito described McDonald as “a community activist involved with alternative policing strategies, and his efforts to improve his neighborhood have subjected him to violent threats from drug dealers.”

McDonald’s right to self-defense in his own home is just as fundamental today as it was for the freed slaves following the Civil War, according to Alito. The Second Amendment right to bear arms is the logical, legal solution, he reasoned: “If, as petitioners believe, their safety and the safety of other law-abiding members of the community would be enhanced by the possession of handguns in the home for self-defense, then the Second Amendment right protects the rights of minorities and other residents of high-crime areas whose needs are not being met by elected public officials.”

Emmett Louis Till (1941–1955) was murdered in Mississippi at age 14. Two white men were acquitted of murder, then later admitted to the killing in a magazine interview.

Emmett Louis Till (1941–1955) was murdered in Mississippi at age 14. Two white men were acquitted of murder, then later admitted to the killing in a magazine interview. Justice Thomas expands on Alito’s historical analysis, covering the period before the Civil War all the way to the murder of Emmett Till in 1955. Beginning with the Antebellum period, Thomas wrote that Southern legislatures, fearful of slave rebellions, enacted harsh measures to keep both slaves and freedmen unarmed. “After the Civil War, Southern anxiety about an uprising among the newly freed slaves peaked. As Representative Thaddeus Stevens [a Republican from Pennsylvania] is reported to have said, ‘when it was first proposed to free the slaves, and arm the blacks, did not half the nation tremble? The prim conservatives, the snobs, and the male waiting-maids in Congress, were in hysterics.’”

Both Thomas and Alito detail the Colfax Massacre, in which a white paramilitary group murdered as many as 165 black Louisianians on Easter Sunday, 1873. The incident was preceded by a rigged election and conflicting claims to the state and local governments in Louisiana. In Grant Parish, the pro-Reconstructionist, Republican faction occupied the courthouse under the protection of local members of the state militia, which consisted mostly of black freedmen. The White League placed the courthouse under siege and succeeded in driving out its defenders. After the black militiamen surrendered, the whites massacred them.

One of the white henchman, Bill Cruikshank, “himself allegedly marched unarmed African-American prisoners through the streets and then had them summarily executed,” Alito wrote. “Ninety-seven men were indicted for participating in the massacre, but only nine went to trial. Six of the nine were acquitted of all charges; the remaining three were acquitted of murder but convicted under the Enforcement Act of 1870 for banding and conspiring together to deprive their victims of various constitutional rights, including the right to bear arms.”

In 1876, the Supreme Court overturned the convictions in United States v. Cruikshank. The Court held that the white militia members had not deprived the victims of their privileges as American citizens to peaceably assemble or to keep and bear arms. The Cruikshank case, according to many historians, marks the end of Reconstruction, the beginning of the “Jim Crow” period in the South, and the gutting of the Fourteenth Amendment.

“Cruikshank is not a precedent entitled to any respect. The flaws in its interpretation of the Privileges or Immunities Clause are made evident by the preceding evidence of its original meaning,” Thomas wrote. Further, “Cruikshank’s holding that blacks could look only to state governments for protection of their right to keep and bear arms enabled private forces, often with the assistance of local governments, to subjugate the newly freed slaves and their descendants through a wave of private violence designed to drive blacks from the voting booth and force them into peonage, an effective return to slavery. Without federal enforcement of the inalienable right to keep and bear arms, these militias and mobs were tragically successful in waging a campaign of terror against the very people the Fourteenth Amendment had just made citizens.”

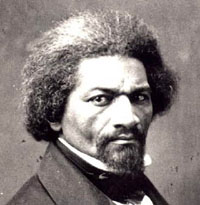

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), the iconic abolitionist and intellectual, was quoted by Justice Clarence Thomas in McDonald v. Chicago:

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), the iconic abolitionist and intellectual, was quoted by Justice Clarence Thomas in McDonald v. Chicago:“The Legislatures of the South can take from him the right to keep and bear arms, as they can – they would not allow a negro to walk with a cane where I came from.”

Thomas continues: “Organized terrorism proliferated in the absence of federal enforcement of constitutional rights. Militias such as the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camellia, the White Brotherhood, the Pale Faces, and the ’76 Association spread terror among blacks and white Republicans by breaking up Republican meetings, threatening political leaders, and whipping black militiamen. These groups raped, murdered, lynched, and robbed as a means of intimidating, and instilling pervasive fear in, those whom they despised. The use of firearms for self-defense was often the only way black citizens could protect themselves from mob violence.”

The history and the experience of African-Americans all point to the conclusion, according to Thomas’s analysis: Disempowering blacks meant disarming them; and now, protecting the right to bear arms is essential to their continued re-empowerment.

‘Amateur’ history

Dissenting Justice John Paul Stevens said the majority’s focus on history was excessive, distorted and misplaced. He accused his opposing justices with abdicating their proper role as interpreters of the law in favor of playing “amateur historians.” Instead, he said the Court should focus on rigorous legal analysis and case precedent — the traditional role of judges.

“The judge who would outsource the interpretation of ‘liberty’ [as it would apply to personal gun ownership] to historical sentiment has turned his back on a task the Constitution assigned to him and drained the document of its intended vitality,” Stevens said. “It is not the role of federal judges to be amateur historians.”

Stevens charged the Court majority with cherry-picking certain historical events while ignoring others — most notably, the long historical record of state and local gun regulation, which heretofore had withstood judicial scrutiny.

— Justice John Paul Stevens

“The Court hinges its entire decision on one mode of intellectual history, culling selected pronouncements and enactments from the 18th and 19th centuries to ascertain what Americans thought about firearms,” Stevens wrote. “From the early days of the Republic, through the Reconstruction era, to the present day, States and municipalities have placed extensive licensing requirements on firearm acquisition, restricted the public carriage of weapons, and banned altogether the possession of especially dangerous weapons, including handguns. Although it may be true that Americans’ interest in firearm possession and state-law recognition of that interest are ‘deeply rooted’ in some important senses, it is equally true that the States have a long and unbroken history of regulating firearms. The idea that States may place substantial restrictions on the right to keep and bear arms short of complete disarmament is, in fact, far more entrenched than the notion that the Federal Constitution protects any such right.”

The Court’s dwelling on the post-Civil War era and mob violence against African-Americans distracts from the factual issue presented in the McDonald case: an individual seeking to protect himself against criminal gangs and drug dealers in the inner-city — a very different problem than what African-Americans faced during the late 19th century. Superimposing the Reconstruction era over contemporary America is an improper fit, according to Stevens.

“The reasons that motivated the Framers to protect the ability of militiamen to keep muskets available for military use when our Nation was in its infancy, or that motivated the Reconstruction Congress to extend full citizenship to the freedmen in the wake of the Civil War, have only a limited bearing on the question that confronts the homeowner in a crime-infested metropolis today. The many episodes of brutal violence against African-Americans that blight our Nation’s history, do not suggest that every American must be allowed to own whatever type of firearm he or she desires — just that no group of Americans should be systematically and discriminatorily disarmed and left to the mercy of racial terrorists,” Stevens wrote.

“And it makes especially little sense to answer questions like whether the right to bear arms is ‘fundamental’ by focusing only on the past, given that both the practical significance and the public understandings of such a right often change as society changes. What if the evidence had shown that, whereas at one time firearm possession contributed substantially to personal liberty and safety, nowadays it contributes nothing, or even tends to undermine them? Would it still have been reasonable to constitutionalize the right?”

See Justice Stephen Breyer's dissent here.

More analysis of McDonald v. Chicago

Part I: From gun rights to religious liberty

Legal theories in recent First and Second Amendment cases shed light on ‘judicial activism’ vs. restraint

Part II: ‘Clausal warfare’

Debate about arcane legal concepts reveals justices' philosophy on fundamental rights

Part III: Originalism and African-American history

For justices who follow ‘originalist’ thinking, history reveals the law